Last week I wrote a post for ArtFCity titled "A Look at The Creative Time Summit: Gentrification, Gentrification, and Gentrification." I was asked to do something relatively short and straightforward but managed to write myself into a corner, turning the post into something long, difficult, even a little scary. "Gentrification" is an umbrella term that covers a constellation of assumptions and biases - the great majority of which I find wrong-headed and vexing. According to Wikipedia, the term "gentrification" was coined by the British sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964. That it is a derivative of "gentry," itself, clearly signals that ownership was core to its original meaning. It was used by Glass to refer to the threat posed to lower-class worker residents, who depended on public housing, by the then fast-growing middle-class residents who, increasingly, could afford to own housing. Gentrification names a brand of class conflict, not an invasion of a bourgeois horde. But not surprisingly Americans have ever used the word gentrification the way the Brits originally intended. In the US race has always been a stand in for class. So US speakers use "gentrification" as a coded way to say "white people" much the same way they use "urban" as a coded way to speak of "black people." And like all coded language, the term "gentrification" obscures and disguises more than in communicates.

According to the art historian, Rosalyn Deutsche, “gentrification” was adopted by New Yorkers in the early 1980s where the “term was used primarily in a celebratory spirit.” It is safe to assume that what was being celebrated was the possibility of white people returning to New York City after white flight had hollowed out much of the city's middle class. [Again this is because race and class are synonymous in the US, even though in reality they are not interchangeable.] But the celebration didn’t last, already by 1984 Deutsche and her coauthor Cara Gendel Ryan were pissing in the neoliberal tureen, with an article for October 31 called “The Fine Art of Gentrification.”

The representation of the Lower East Side as an "adventurous avant-garde setting," however, conceals a brutal reality. For the site of this brave new art scene is also a strategic urban arena where the city, financed by big capital, wages its war of position against an impoverished and increasingly isolated local population. The city's strategy is twofold. The immediate aim is to dislodge a largely redundant working-class community by wresting control of neighborhood property and housing and turning it over to real-estate developers. The second step is to encourage the full-scale development of appropriate conditions to house and maintain late capitalism's labor force, a professional white middle class groomed to serve the center of America's "postindustrial" society.Gentrification reading, then and now.

In her 1998 book, Evictions: Art and Spacial Politics, Deutsche discusses many of the same issues discussed at the CTsummit and, discusses them, in much the same way. (One curious difference: homelessness, one of the central concerns of Deutsche's book, didn't come up at any of the presentations of panels I attended.) This both speaks well of how far ahead Deutsche was in her thinking, and how stalled the rest of us are in ours. As more than one speaker at the summit reminded us, gentrification requires collusion of politicians and developers, it is not inevitable process. But that was not the impression communicated by CTsummit. With the exception of the presenters from Detroit MI (who spoke of staving off urban collapse), and Braddock PA (who spoke about recovering from collapse), gentrification was where one presentation and discussion after another came to rest. If not an inevitable process of urbanization, gentrification seems to be the inevitable conclusion to any discussion of urbanism.

The problem for me as an artist, is that the framing device of gentrification cast art's urban role was in one of two ways. The first, default role, artists can play is to enable gentrification - or, as the keynote speaker Lucy Lippard characterized artists' role, we are “the flying wedge of gentrification.” This is one of those magical places where the Hard Left and Hard Right agree. They both see artists as the mysterious first step in the life cycle of chain restaurants and big box stores. The second possible role artists might play, according to the CTsummit, is for artists to act as a heroic resistance to gentrification. The second role is doubly vexing for this urban artist. First, because as a New Yorker of a certain age I have first hand memories of the old Times Sq., and the random violence and petty crime that surrounded it. And second, because as an artists, I've never been convinced by the common understanding of the "SoHo Effect" (the birthplace of the flying wedge metaphor), but I am very sure that no one, inside the CTsummit or anywhere else, has a clear idea of how artists might actually stem the tide of white residents to desirable low-income Brooklyn neighborhoods.

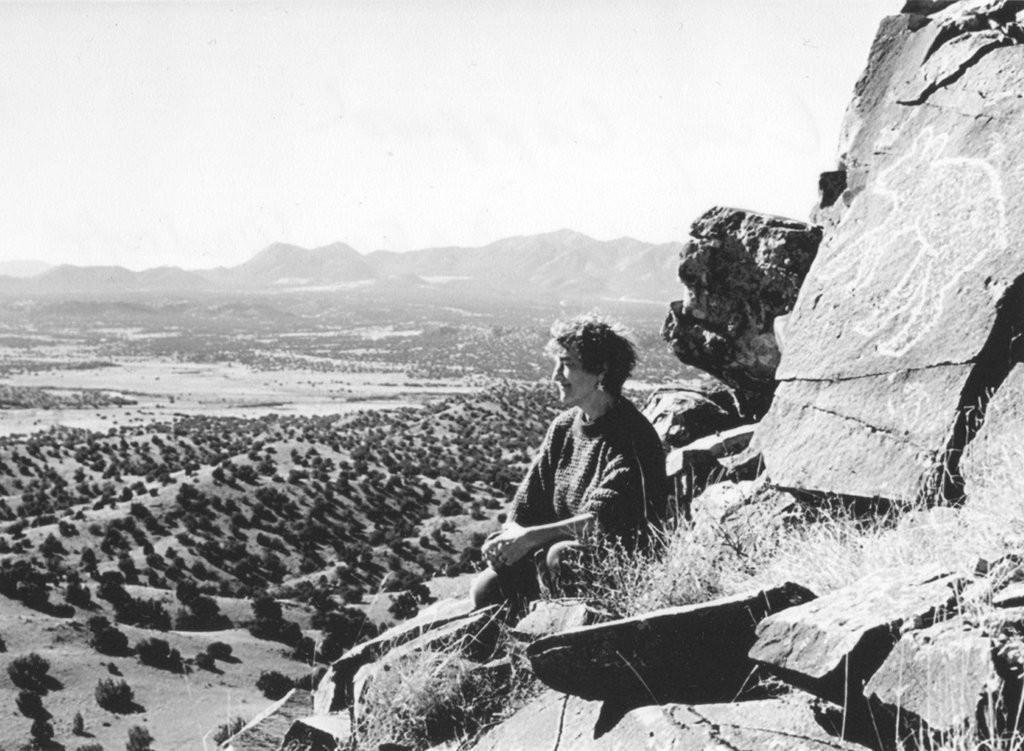

Lucy Lippard, who humble bragged about her children playing in glass strewn Tompkins Sq Park sand boxes, is now gentrifying the hell out the great Southwest.

The problem with gentrification as an inevitable conclusion is that the binary choice it presents us is a false one. While "integration" is a historical lame duck in America, I think it is the better way to think about how artists and arts organizations can help shape thriving cities as well as how to intervene in collapsing and collapsed cities like Detroit and Braddock, that don't yet have the luxury of worrying about large influxes of young high earners of any color.

As I argued in my AFC post, the choice gentrification offers arts - as either corporate shills, or as anti-bourgeois bulwarks - is self destructive one for urban artists who depend on urban infrastructure. Rich people can (and do) abandon public infrastructure when the going gets tough, poor people can't (and don't). And when rich people abandon cities' transportation, education, and police systems, those systems die - as it did in Braddock, and as it is doing in Detroit. But not only don't I buy the idea of artists as bulwark, I don't buy the consensus interpretation of the SoHo Effect - that the presence of an artists enclave helped revitalize a city blighted by deindustrialization and "white flight". New York's current good fortune is due, at least in part, to the fact that it was one of the few cities in America that didn't totally implode during the era of deindustrialization and white flight.

Pruitt-Igoe Myth [St Louis's disastrous response to white flight was to build thousands of new housing units.]

While I am not an expert in rent law, I suspect that part of the reason for that stability was New York's rent-control laws. Unlike cities like St Luis, that imploded due to deindustrialization and white flight, enough middle class New Yorkers refused to abandon their rent-controlled apartments, no matter how much blood was in the streets. Every story of white flight has stories of lone hold outs - isolated refuseniks (usually elderly) who were powerless to alter the changes taking place around them. But in NYC there were tens of thousands (of all ages and income brackets) who were incentivized to stick out the rough years. Those masses of holdouts were like beachgrass - their roots anchored the city around them and preventing the sorts of total collapse that rocked cities like St. Luis, Detroit, and Braddock are still working to recover from. And while many of New York City's rent laws have been "liberalized" - making it easier to force up rents and evict tenants - I expect that tenant protections are still stronger here than most other US cities.

And while the "SoHo effect" was mentioned repeatedly at the CTsummit - it was used only in the conventional sense of Lippard's flying wedges. No one mentioned the 1982 Loft Law that gave SoHo tenants protections from unfair rent hikes, or that, because SoHo wasn't a top-down development scheme, many artists were able to buy in SoHo before the speculators arrived. And while SoHo is no longer a gallery district, it is still home to many aging artists. Probably just as many have sold their lofts for millions and built rural studios upstate. But those sell-outs form a powerful web of artworld influence all around NYC. My issue with the SoHo Effect is that most observers (pro & con) point to it as an example of free market forces and massive turnover, but that is because they are focused on the area's commercial tenants. But because of zoning and rent laws, the upper residential stories are a very different narrative, one of regulatory forces and relative stability. Artists in SoHo have been more like anchoring beachgrass than flying wedges. They have anchored a neighborhood buffeted by change, and when they left, they enriched the region.

Competing visions of The Rent is Too Damn High - I prefer Matt Yglesias

The only CTsummit presenter who focused on the importance of rent laws at all was Jimmy McMillan - of "The Rent Is Too Damn High" fame. I'd seen McMillan hectoring small crowds around the city on a number of occasions and written him off as a buffoon. And while his presentation hinted at buffoonery (alluding to total amnesia since 'Nam), McMillan seemed to know his stuff when it came to the peculiarities of NYC rent laws. The SoHo effect should be reconsidered now as a public sector victory. If artists see them selves in terms of gentrification - cast them selves as a resistance working against politician colluding with capitalists - the lesson gets lost. It also means the the best artists can hope for is to work around government, rather than finding a way to work with it.

Recently the artist Bill Powhida introduced me to an idea he had been rolling around. He dubbed his concept a "Yellow Building" - the name of which is intended to evoke LEED certified "Green Building." Bill's idea is to achieve financial sustainability via a contractual mechanism; for a building to own itself. It was Bill's solution to the problem of creating a stable affordable place to work in the face of ongoing gentrification.

Let's call the problem that Bill and his friends are trying to solve, the "Bushwick Effect." The problem for this cohort of artists is that because of the expectation for profits created by the SoHo Effect, most of them were never able to buy their work/live spaces - speculators were there first. Additionally, many live, like Bill, in building with less than 6 units, and therefore are without all but the most basic rent protections as well. And so, like Bill, this current generation of artists can look forward to being forced out of neighborhoods, they helped "gentrify" by wealthier non-artist "gentrifiers" (more about those scare-quotes in a moment). Bill's aim, is that Yellow Buildings could be tool to give artists affordable places to work and live within the city - for a life time. The the realistic expectation, that Yellow Buildings are intended to work-around, is that the city will become unaffordable to artists (and other low-intensity income earners).

I like Bill's idea, and would love to see it realized. Like SoHo, with its population of aging artists in magnificent million-dollar lofts, Yellow Buildings might help a few dozen artists (hopefully Bill being one) to bridge the lean years into their late-career florescence and beyond. Bill's hope is to use "tools of capitalism... to challenge what ownership means." This is an extremely lofty goal (which Bill freely acknowledges) and are clearly intended to be a response to the problem of gentrification. But the problem with "gentrification" - as a conceptual frame - is that it sets up someone like Bill, who teaches art in NYC public schools and is a consciences and politically active member of his community, to feel guilty about his place in a city that needs him and more people like him desperately.

The portrait of a generation: William Powhida and Jade Townsend, Art Basel Miami Beach Hooverville (2010)

As I told Bill, as much as I like Yellow Buildings, I don't think they will scale in any way that will be meaningful to the health of the New York artworld, much less for health of New York City (both of which I know Bill cares about deeply). If anything, by locking in artists at affordable rates, in the sort of low old buildings that he and I and other artists prefer to work in (like -1027 Grand Street - that Bill has used to illustrate his Yellow Building Post), Yellow Buildings will make housing in surrounding areas more expensive for low-income earning non artists.

I understand that this conclusion is counter intuitive - or at least it runs counter to one of the founding myths of gentrification that intuitively feels right. Jane Jacobs belief that "new ideas need old buildings" is the sort of thinking that gives anti-gentrifiers their raison d'être. Jacobs valorized the exact sort of low old pile that Bill and I, and pretty much every other artists covet as work spaces (and that hedge fund managers and dot com millionaires covet as bachelor pads). In his book, Triumph of the City, the economist Edward Glaeser makes the case against these old low stone piles:

Jane Jacobs liked protecting old buildings because of a confused piece of economic reasoning. She thought that preserving older, shorter structures would somehow keep prices affordable for budding entrepreneurs. That’s not how supply and demand works. Preserving an older one-story building instead of replacing it with a forty-story building does not preserve affordability. Indeed. opposing new building is the surest way to make a popular area unaffordable. An increase in the supply of houses, or anything else, almost always drives prices down, while restricting the supply of real estate keeps prices high.Tyree Guyton, Project Heidelberg

Since taking office in 2002 Mayor Bloomberg has "spearheaded the largest rezoning agenda since 1961 – now comprising 123 rezonings covering nearly 11,500 blocks." That legacy effects all five boroughs. Rather than heroically derailing tomorrow's private development schemes the way artists in the 70s and 80s derailed yesterday's public building programs, I'd like Mayor-Elect Bill de Blasio to be pressed to give art a place within the plan. What Bloomberg recognized, was that if NYC is going to absorb a million more residents by 2030, we need to act in order to relieve the market pressure on the existing housing stock. His plan, to build a lot more tall towers, and to spread that development along subway lines to every part of the city, was a good begining, but not a perfect one. It can and must be improved.

Whatever happens, we are going to be OK

Bill Powhida began imagining his solution to the Bushwick Effect, then actively pursuing solutions with a group of his friends, and finally laid them all out for me over beer, all long before any of us could have predicted de Blasio's primary victory. My immediate reaction was that Bill and his friends should put their energies into pressing the city to create "incentive zoning" that would benefit developers and artists, as well as indirectly benefiting other non-artist low-income earners. Call my plan, "Yellow Mezzanines." It would be to allow developers to build taller luxury towers, with fewer setbacks (because I fucking hate hate hate setbacks), in return for providing large amounts of long-term, rent-stabilized, spaces to artists and arts organizations.

The city has provided incentive zoning for decades in order to encourage developers to create public space in densely built sections of the city. I am not a fan of "vest pocket parks" and "public atriums" as replacements for actual public space. But setting aside the 2nd 3rd, and 4th floors of a new tower for light-industrial artists studios, in trade for ten more stories of prestige residential space up top for developers, is a far better deal than a pocket park for the long term health of the city.

And it's win-win for developers. They can give artists a poor door and no one will bat an eye. Not because artists aren't poor, we are poor. Artists are poor people that rich people aren't afraid of. As long as the poor-door has a loading dock and a hefty 24 hour freight elevator, the artists will love it. And unlike traditional subsidized housing, artists need no frills - ideally the city would allow Loft Law-like exemptions so Yellow Mezzanines would be occupy-able and bare bones: cement floors, exposed pipes and conduit, and large undivided spaces, big windows

Norman Foster's WTC proposal for twin "kissing" towers would have made great artist studios.

[I should admit that this was essentially the same proposal I made twelve years ago when everyone believed that no one would every willingly occupy the top floors of a WTC tower rebuilt to the height of the original Twin Towers. I argued we could have build them even taller as long as the upper most vacant floors were made available to artists for a nominal $1 a sq foot. The building would have been fully occupied on day one. Here I'm just putting artists at the bottom rather than the top.]

Yellow Mezzanines don't alleviate the need for the city to find a way to again build traditional subsidized low-income housing for non-artists, but it doesn't make life harder for those non artist low-income renters either. Any plans to set aside real estate for artists enclaves would do just that. But conversely, artist can't use conventional low-income housing.

Additionally, integration makes for a better city. In his 2005 book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, the author Jared Diamond argues that one of the primary reasons societies have collapsed in the past is that wealthy elites isolate themselves; they retreat into worlds of their own and lose touch with the problems of the societies that support them. He doesn’t use the example of Battery Park City and Riverside South, but he could have - both are Giuliani-era ghettos for the wealthy out-of-touch. These isolated enclaves of the rich should be recognized as being just as septic to the body politic of the city as ghettos of the very poor are.

Battery Park City is Manhattan's Green Zone, for those who want the advantages of NYC with out all the mess of actually living here.

While its not perfect, I prefer Bloomberg's plan to integrate high-income earning residents in luxury high-rises, along subway lines, all throughout the city. One assumes doorman high-rises are especially attractive to new comers who might otherwise find living in NYC for the first time daunting. And so long as they are sharing the subways with the rest of us, they are bound to figure out that how to be real New Yorkers. And while I like Bill's plan, I prefer one where artists and art organizations have stable places to call home throughout the five boroughs, and can act, throughout the city, as rooted anchors for the changes expected to buffet us for decades to come.

As I wrote in the AFC post, the CTsummit’s title "brought to mind the fact that 3.3 billion new city dwellers will be added to the planet over the next 40 years, and do so during a period of environmental change, continued political turmoil and technological transformation." My solution to the Bushwick Effect, is built on a facet of the SoHo effect that is very well understood: that cities around the world tried to imitate New York's success. Whether or not they succeeded isn't important, its the fact that municipalities that had been buffeted by deindustrialization, were shown a novel way to reuse industrial building stock.

Art walks, First Thursdays, Art Prize - these are all part of SoHo Effect. I imagine the solving the Bushwick Effect could be far more meaningful. If NYC shows that integrating art and artists - city wide, for decades at a time - can be as successful in the 21st Century as an artist enclave was in the 20th, other cities might see the wisdom in rent control. Cities change, not all change is good, but all change is disruptive. Robust cities are able to absorb the shock of both goods and bad fortune. The Twenty First century cities will need artists because we can help them absorb the shocks of change. But it will require artists to stop imaging ourselves as flying wedges, and instead get on with being rooted anchors.

William Powhida, Why Are Artists Poor (2012)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment